A tongue in every star that talks with man,

And wooes him to be wise? nor wooes in vain;

This dead of midnight is the noon of thought,

And wisdom mounts her zenith with the stars.”

― Anna Laetitia Barbauld

by Eugene Robin, CFA | Principal, Research Analyst

When it comes to investing, it is our firm belief that there is a lot of value in doing our own work and keeping our own counsel. However, in doing so, we risk making terrible mistakes by burying our heads in the sand and not paying attention to anyone and anything around us. Naturally, there is no 11th Commandment that we are aware of, so each instance requires its own determination.

Which brings us to a short-selling report that came across the Bloomberg on one of our largest holdings: ViaSat (Ticker: VSAT). Why bother responding, one side of the satellite analyst asks? This Kerrisdale Capital is another 56 page pile of crap neatly distributed by someone who is already short the stock and has now sent the pitch into the global ether to hammer it for a few days (or weeks) and then cover. Nice trade, dude.

I will note that this is the firm that made an eloquent pitch for the short-sale of Straight-Path at $34 before a ferocious bidding war by somewhat informed industry punks like Verizon and AT&T, and the same firm that recommended shorting Dish Networks at $44. It was nonetheless suggested to me by someone at our firm named Jeff that since this is our largest position, I might want to ignore the source of the information and focus on a fresh “what-if?”

Hey, he is paying. And of course he is right! And being right has no title or pedigree. So as the lead analyst on VSAT for our firm, I committed to stepping up to the plate and preparing a written response for our investors and some of their consultants, some of whom may have inquired about the piece. (Spoiler Alert—buy the stock.)

1. The Cardinal Big Picture Mistake

Kerrisdale seems to focus almost entirely on the consumer broadband offering of the ViaSat-1, almost ignoring the fact that 44% of VSAT is a defense business with a $633 million backlog worth 53% of the current value of the stock. We could pick up the phone and have 8 bidders within the week if we thought we could get paid for it. As a “valuation short” that fails to conduct a proper sum-of-the-parts analysis, this is sloppy at best.

2. ARPU Math or Lack Thereof

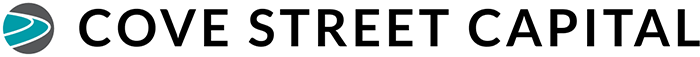

Kerrisdale makes some blistering allegations about ViaSat’s increasing ARPUs (Average Revenue Per User), suggesting that the numbers are overstated and thus bound to fall. We looked at the short seller’s assumptions and had a few questions of our own. The entirety of Kerrisdale’s ARPU point is based on the following flawed analysis:

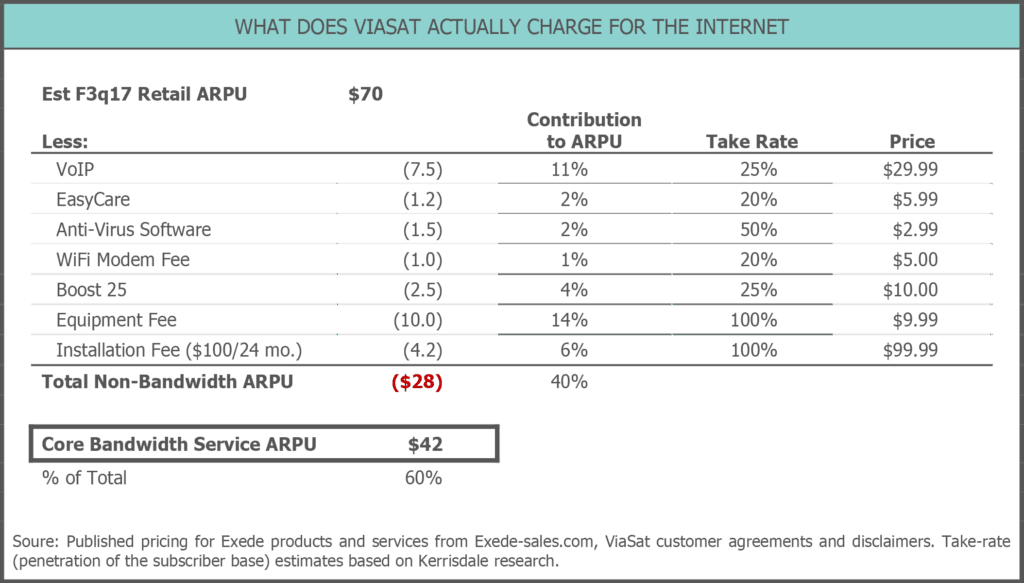

A brief mathematical point first: the actual retail ARPU (the starting point of their calculation) is closer to $80, not $70. Specifically, ViaSat’s blended ARPU is $66 and if retail ARPU were only $70 that would imply that Kerrisdale believes ViaSat’s wholesale distributors deliver it $56.67 per sub, a number almost double the true value (based on ViaSat’s roughly 70/30 split of retail/wholesale). In fact, the COO, Rick Baldridge mentioned in September of 2014 at the Bank of America Media Conference that “our average wholesale ARPU is under 30”. Therefore, if you plug in $30 for wholesale ARPU at a 30% weighting, you get retail ARPU at around $80. Strike one, Kerrisdale.

Besides this poor math, the rest of Kerrisdale’s breakdown is entirely fictitious. The take rates of the VoIP, EasyCare, AV, WiFI Modem, and Boost 25 are entirely made up. There are no publicly available data sets that would indicate that half of customers take anti-virus protection and a quarter subscribe to VoIP. To see how much influence these ancillary services have had on ARPU, we have decided to back into numbers from our own research. If you look at the mix shift that has occurred since day one—with ViaSat relying less on wholesale and more on retail—you see that roughly $2.60 of increased ARPU comes from shifting from 37% wholesale (Q2 2013 call) to 30% wholesale (company stated June 2017):

So, if blended ARPU was $54.50 in Q4 2015, and $66 in Q4 2017, and $2.60 of that increase was simply a mix shift, then that leaves $8.90 in possible ARPU gain from ancillary services. Additionally, this analysis does not include any incremental from customers “trading up” plans and choosing higher tiers of service. (It effectively freezes the same mix of plans that existed in 2015 and assumes the same mix exists in 2017.) ViaSat has repeatedly mentioned that higher-value/bandwidth plans are the singular force driving ARPU (and by repeatedly, we mean every quarter). So part of that $8.90 comes from people choosing higher cost but higher bandwidth plans. This is problematic for Kerrisdale’s narrative since they claim that ancillary plans are providing $13.70 in ARPU, a sheer mathematical impossibility. Therefore, if only half of that $8.90 is due to ancillary services, you have penetration/take rates of less than 10% for each product!

Why is this important? This is important because Kerrisdale’s ARPU decline-focused narrative is predicated on an overextension of these services and a “core” ARPU of only $42. In reality, the core ARPU appears to be closer to $60, with the actual penetration levels of the value added services providing a vast runway to increase ARPU, not the opposite. If VSAT had penetration rates similar to Kerrisdale’s analysis, its blended ARPU would be approaching $75. Here’s to Kerrisdale being right!

3. IS ViaSat Really Losing Ground to Competition?

First, we should define the competition set within consumer broadband: Is the competition urban cable MSOs and fiber providers? No. Is the competition 4G/LTE? No. (We’ll get to this point later.) Providers who service roughly 10% of the households in the United States, with services ranging from DSL (all flavors of DSL) to satellite, encapsulate the competition (i.e. Hughes). Thus, the real question surrounds whether ViaSat’s services are losing ground there. We argue that this is far from the truth—with some important caveats.

DSL providers are painted by Kerrisdale as amazing competitors that are capable of immense feats of technological change and evolution. The reality is quite the opposite. DSL speeds, as served up by the most common ADSL technology, have not budged for years. Since the FCC started their Broadband Report in 2011, DSL speeds have not moved. At all.

The only things that have changed in that world are: (1) the inclusion of a different AT&T product as “DSL” by the report (U-Verse, which is VDSL) and (2) the acquisition of Qwest by CenturyLink that artificially boosted CenturyLink’s performance by including a top tier urban-based Qwest offering that isn’t available to the core CenturyLink customer. Net-net, the average DSL customer today is still getting the same 4-10 mbps connection they were getting in 2011.

We find that, over the course of our reports, the overall annual increase in median download speeds by technology has been 21% for DSL, 47% for cable, and 14% for fiber. The large apparent increase is DSL speeds is largely driven by our change in methodology for reporting on AT&T and the relatively large market share for IPBB (IP Broadband). The apparent increase in DSL speeds for CenturyLink is the result of a merger with Qwest (now included as CenturyLink). For the majority of ISPs using DSL, there has been little change in speeds over the course of these reports.

— 2016 FCC Broadband Progress Report

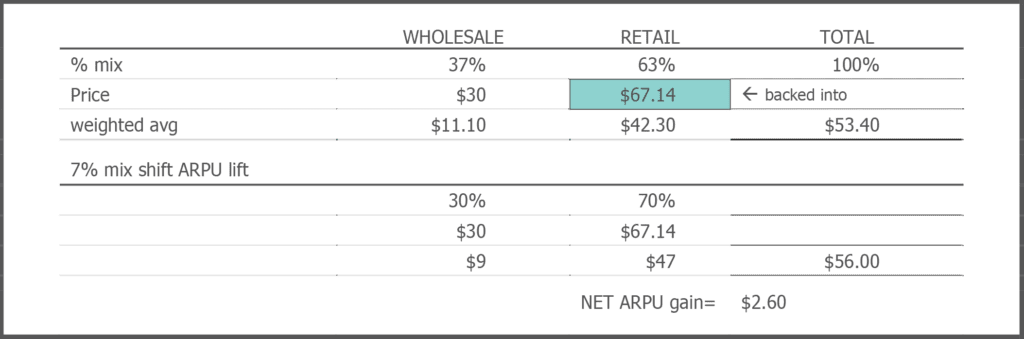

So where does Kerrisdale come up with its claim that by 2020 DSL will somehow serve up 250 mbps (on their page 18, chart)? Kerrisdale conflates DSL with VDSL without grasping the nuances of the actual technology. VDSL, or very-high-bit-rate DSL, allows for immense speed via copper wire delivery à la “shortening the loop.” What that entails is bringing fiber access closer to the point of delivery (your home), cutting the length of copper wire needed to deliver data, and enabling data speeds that blow even cable out of the water. Kerrisdale’s DSL claims are entirely based on the prevalence of VDSL and its offshoot VDSL2 (which is a bonded pair of VDSL, or two VDSL lines slapped together).

However, there is a major flaw in that assumption—VDSL/VDSL2 only work with a fiber-to-the-node/curb infrastructure in place. Said another way, you can’t have VDSL without laying fiber down the street first. This makes VDSL/VDSL2 impractical in all but the main metropolitan areas (think top-40), where ViaSat doesn’t have a footprint to begin with. The length of copper wire to the home materially impacts bandwidth delivery capabilities for DSL. Thus, the farther you are from a fiber drop point the less likely you are to achieve even 20 mbps. (The cutover point is between 1,000-1,800 meters depending on the technology deployed—see chart below.) Kerrisdale’s exaggerated claims aren’t actually relevant to anyone living outside of the main metro areas, and are preposterously exaggerated when comparing ViaSat’s Exede’s per bit economics.

Given all of the preceding, we see Hughes’ competitive offerings as the true governor of ViaSat’s growth. Hughes has gained ground over the past two years thanks to the new Jupiter constellation satellite,s as well as the “real” DSL as personified by traditional ADSL offerings. Hughes offers up 25 mbps on their latest satellite and ADSL’s top tier maxes out at 24 mbps (theoretically—the actual deliverable is probably 90% of that). VSAT-2 is perfectly aligned against both offerings. We will also add that VSAT-2 can serve more customers per dollar spent than Hughes can, given the actual throughput capacity of VSAT-2 versus an average Jupiter satellite.

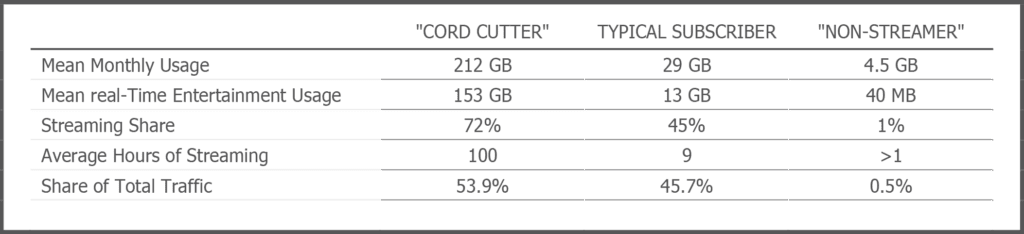

One other point of contention that we found in Kerrisdale’s analysis is their liberal use of averages. For example, they quote the statistic that the average household data consumption in the U.S. has hit 190GB per month, while ignoring the actual distribution of usage. It is well known that the top 20% of users account for a vast majority of the traffic in a given network—ViaSat’s included.

In a 2014 study published by Sandvine, an internet traffic analysis firm, it was found that the typical subscriber in the networks they monitor actually only uses 29GB of data, while the top tier “cord cutters” use 212GB. Sandvine had the following to say about the skewed nature of usage distribution: “The top 5 percent uses an average of 328GB a month, with 250GB of that coming from streaming audio and video. The top 10 percent uses an average of 247GB a month, with 182GB coming from streaming audio and video.” (Ars Technica, 2014) Our guess is that the median of the data set Kerrisdale references is much lower than 190GB. Comcast, a fixed cable provider, has itself mentioned that its median user uses 75GB per month. (Wired Business, 2016)

Kerrisdale accurately points out that ViaSat’s performance metrics have dropped from the initial rollout of the service in 2014. Yet, this should not be a monumental surprise given that the second satellite was supposed to be operational by now (if not for the SpaceX and Arianespace issues) and that the first one was at full capacity in terms of its consumer allocation as of January 2016. Recall that over the past 18 months, VSAT-1 has managed to “turn on” on over 125 additional aircraft as well as commenced service to military customers. If there wasn’t any performance loss on the existing consumer base we would have been astounded, given the load required to implement the additional capabilities VSAT-1 provides.

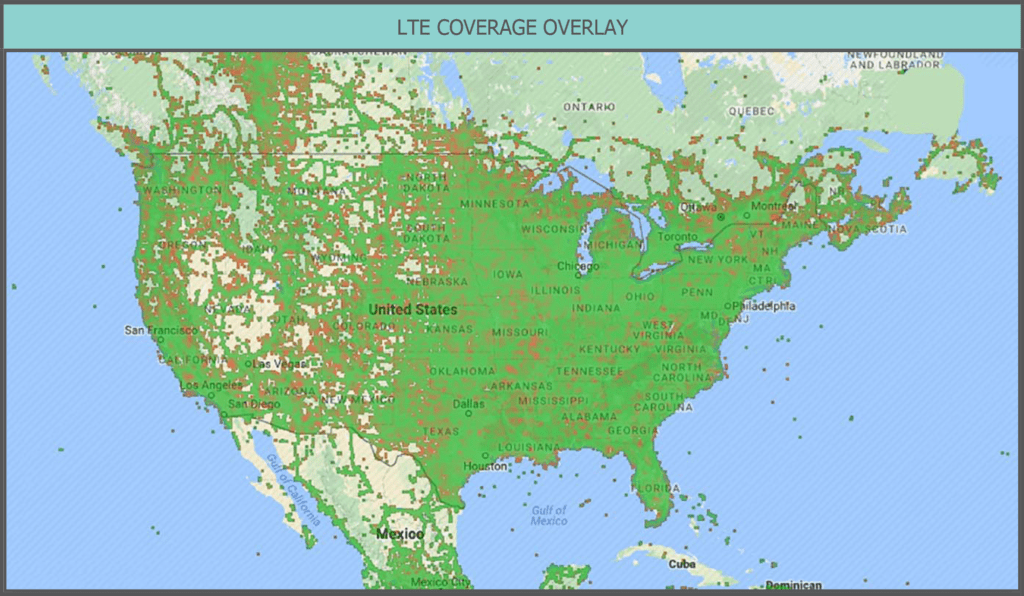

Lastly, as a small aside on wireless competition, we would like to point out that if wireless offerings were such a threat then all of rural America would already be connected to data provided by LTE carriers. Viewed from an availability perspective, LTE is ubiquitous at this point (see map below of the overlay of all four carriers’ LTE coverage), and yet the number of people receiving their daily dose of the internet solely from LTE is not 100%. Strange. Maybe Kerrisdale should instead focus on the economics of LTE carriers’ spending, inclusive of the cost of spectrum, to see why it would make zero sense for any of the Big Four to build out a robust network in rural areas that have densities of less than 10 people per square mile (as opposed to an urban network).

In conclusion, nothing the short report references is an indictment of ViaSat’s technology or points to “lost competitive ground” versus viable alternatives in any way.

4. ViaSat Subscriber Growth Not an Issue

Kerrisdale accurately identifies the following phenomena in satellite land: 1 + 1 = 1.8. What this means is that adding VSAT-2 to the existing VSAT-1 doesn’t linearly increase the subscriber count; ergo the subs don’t go from 650K on VSAT-1 to 1.3mm on 1 & 2 combined. What happens is that part of the bandwidth economics of VSAT-2 are “given up” to support higher quality plans for existing subscribers on VSAT-1. This isn’t news and has been repeated by the company over the past year. It isn’t ViaSat’s fault that analysts don’t listen.

Is this an issue? We believe the answer is a definitive no. Our model has the combined satellites getting to 1.05mm subscribers by the time VSAT-3 is launched. Our roughly 50% growth in subscribers is entirely doable (see the TAM discussion) and misses the increasing ARPU and churn reduction VSAT attains from being able to offer up higher speed plans with higher data caps.

Why do we think this way? Simply put, we see a much larger opportunity for VSAT to extend its market relative to the past. If you believe the Kerrisdale narrative, there is no way that subscribers could grow at all in the face of technological progress over the past five years. Yet, if you look at Hughes’ subscriber count in 2012 of 588,000 and WildBlue’s (precursor satellite to VSAT-1) 385,000, you have a total satellite market of about 977,500 customers. By 2017, Hughes had 1,036,000 subscribers and ViaSat had 659,000, for roughly 1.7 million subscribers. This tells us that in the face of all of the technology that Kerrisdale pointed out, the combined satellite subscription count grew at a 12% CAGR.

Of course, one could argue that the past is not prologue. That may well be true but the point we would like to illuminate is that the high growth rate of subscriptions was directly a result of the technological sea change brought on by the creation and launch of VSAT-1. Hughes’ own efforts subsequent to the VSAT-1 launch have been of a very good copycat (aided and abetted by the theft of ViaSat technology by Loral—who built the Jupiter constellation, we should add). The combined efforts of ViaSat and Hughes created a growing market whereby people who once didn’t see satellite as a legitimate product started to switch. We posit that the sea change that the second and third generations of ViaSat satellites will bring about will firmly place satellite connectivity into the mindshare of consumers in select markets. Our net subscriber growth projections are effectively similar to what ViaSat managed to do with the first generation.

There is no real way for us to counter Kerrisdale’s claim that ViaSat’s subscriber growth will not be “meaningful” other than what we’ve laid out and an understanding of what “meaningful” actually means. We will elaborate later in our discussion of Kerrisdale’s TAM the other points that lead us to have greater comfort in our consumer projections.

5. Addressable Market – Some Truth but a Low Hurdle

We take no exception to Kerrisdale’s commentary about the shrinking TAM versus a year or two ago. However, we find several of their claims to be extraordinary and backed up by nothing except a need to create a short narrative.

Examples include:

CLAIM: “The US Government has budgeted close to $2bn a year in subsidies for improving rural broadband access. ViaSat is the only internet service provider without additional capacity – even smaller, low-end DSL and cable providers are accelerating the deployment of technologies that significantly enhance the capabilities of wired networks.”

REALITY: Government subsidies are a giveaway to rural telcos who are not incentivized to do any more than the bare minimum. What is that minimum? It depends. According to the new rural giveaway scheme (ACAM), there are four buckets of minimum service: 25/3 (25 mbps download/3 mbps upload), 10/1, 4/1, and “reasonable request.” The top tier bucket is mandated to be implemented at a 75% rate across densities of 10 households per square mile, with that rate dropping to 50% for 5 households/mile and 25% for anything under 5/mile. This “significant enhancement” is going to be done over ten years. ViaSat is going to provide that speed next year. Again, please re-read our answer to Kerrisdale’s DSL claims to understand the absurdity of the notion that DSL can compete with even a second generation satellite, much less the third generation currently in the works (and only three years out).

CLAIM: “To retain the 659k net customers it currently has, ViaSat had to burn through 1.2m gross customer additions over the past 5 years. We estimate EchoStar, a direct competitor to ViaSat, has recorded roughly 2m in gross adds to achieve its current 1.2m subscriber base. As a result, over 3m people in the last 5 years have been tainted by satellite’s degraded speed, spotty reliability and constraining usage caps.”

REALITY: This analysis ignores the fact that both companies added net subscribers in that period, thus the apparent number of “tainted” users doesn’t yet match the number of users who are “tainted” by the poor performance of DSL. In fact, citing the same FCC report Kerrisdale cites, the average of median download speed over advertised speed attained by the main DSL providers runs between 75-90% for the 1-10Mbps segment of the DSL population. While it is true that ViaSat’s performance fell off for 2016, on an uncongested satellite network they have consistently hit 120-140% of advertised speed category since their service’s launch date.

CLAIM: Because DSL is cheaper, ViaSat cannot capture that share because many DSL subscribers don’t care about speed and are only interested in price.

REALITY: Even using CenturyLink as the reference point, DSL lines have declined at an 8-12% clip annually since the late 2000’s. (Last year, CenturyLink lost 13% of their low bandwidth revenue.) If you look across the RLEC universe (rural telcos), that decline has not abated in any way and is actually accelerating. If Kerrisdale’s claims were true, then this persistent burn of legacy copper lines wouldn’t exist. However, it does exist, and will continue to exist until DSL subscribers eventually approach zero over the very long-term. Does this mean that DSL loses everyone to ViaSat immediately? No. Nevertheless, that’s irrelevant. Our model anticipates an expansion of the net customer footprint by 350,000 over the next three years. If DSL lines are dropping by 10% per year and there are 4-5 million out there per Kerrisdale’s own assertions (which are conjectures based on their own “model” and not facts), then ViaSat has to capture a meager 10% of that market to succeed on a net basis—or a quarter of DSL attrition over the next three years. We’ll be happy to make that bet with Kerrisdale.

CLAIM: There are only 4 to 5 million available subscribers in ViaSat’s TAM.

REALITY: That number is Kerrisdale’s assumption on the rural addressable market. However, as of 2016, the FCC has released a state-by-state analysis of the percentage of the population that doesn’t have access to 25 mbps download and 3 mbps upload speeds. We went state by state to re-create that analysis on a household basis and came up with 12.58 million households that have yet to have access to 25 mbps. (You can recreate the results via using data from broadbandnow.com.) Even if that number shrinks by 40% again over the next two years (a stretch), that would leave 7.5 million households in the TAM. We are not quite sure if the rest of Kerrisdale’s points about “substandard housing” or “15-20% of rural and urban homes are structurally unlikely to ever be served by satellite“ are based on anything except their own assertions, given that DirecTV and DISH have never referred to rural consumers as untouchable due to the nature of their housing stock. Even at 4 to 5 million subs, we are looking at ViaSat capturing 20-25% of the most pessimistic analysis of potential customers out there. Harder but still doable.

6. EBITDA, the Flawed Measure and More Flawed Math

On the question of EBITDA, we whole-heartedly agree with Kerrisdale, but with a caveat. EBITDA is a terrible cash flow proxy to use for companies with large capex requirements, which inevitably translate into high maintenance capex. ViaSat kind of fits this model. It needs lots of capex to launch satellites and thus the depreciation it puts on its income statement is a real cost to the business. However, the real “cost” of the maintaining capex is the issue, not the cost of growth capex in terms of getting the satellite constellation up and running.

For example, if two satellites are all that are required to generate the potential revenue for North America, and if each satellite has a 15 year useful life, then you could make the case that the real cost per year of maintaining the fleet would include the cost of the ground infrastructure as well as an amortized amount for each satellite, or in this case 2*(cost of one satellite / 15). However, there is an issue with doing something this simplistic. A significant issue arises when you think about technological advancement. If satellite 2 has 2x the capacity of satellite 1 and satellite 3 has 4x the capacity of satellite 2, then the depreciation math gets tricky. You would in theory need only a single satellite to offer up the same experience as that of the previous two satellites and thus if you were amortizing the maintenance for the same bandwidth bound network, you would need a significant degree less capex to do so. And if you need less capex, then less depreciation will run through the income statement and therefore “true” cash margins would increase.

Additionally, we pick at another math problem with Kerrisdale’s analysis. Their calculation of CPE (customer premise equipment) depreciation is odd and doesn’t match anything close to what we have in our model or what makes sense given what the company discloses. CPE costs are $450 for the box that ViaSat rolls out to its customers and $150 for install. Through FY2019, when accounting rules change what gets capitalized and what gets expensed, ViaSat runs 2/3rds of that through the investment cash flow section and not through the income statement. Yet, the year-over-year change in accumulated depreciation for CPE is only $21.8 million (2017 10K) and not the $60 million Kerrisdale claims.

How can this be? Kerrisdale forgets to factor in the returned CPE, which is refurbished and recycled back into the CPE population (i.e. new customers). Thus a 2.5% churn effectively reduces the capital outlays and the total additional CPE amortization that is run through the income statement. It’s a minor point but one that is worth understanding, especially since in 2019, per new accounting rules, the company will be forced to capitalize ALL of the CPE expenditures. So, watch for satellite margins to increase and cash flow from investing to decrease.

Our analysis suggests that EBITDA isn’t overstated and if people choose not to look at a cash flow (NOPAT) metric that properly deals with capital intensity then that’s their problem. On that point, Kerrisdale’s NOPAT calculation obviously conflates growth capital with maintenance (as well as other issues such as ARPUs, subscriber acquisition costs, ancillary revenues from military contracts, etc.). We’re not going to get into a spreadsheet nerd battle with Kerrisdale but after reviewing their assumptions we feel much more comfortable with our own value assumptions.

7. International Expansion Claims are Unsubstantiated and Strategy Misunderstood

Kerrisdale’s international opportunity points are mostly fake news. The only factual statement in their analysis is that ViaSat paid 132 million euros for a JV with Eutelsat, and received 49% of the capacity of Eutelsat’s satellite and a European foothold. The rest of their claims are unsubstantiated given that none of the wholesale agreement’s terms (such as the economics of contributing VSAT-3) are public.

Additionally, Kerrisdale misunderstands how Eutelsat operates, and the reasons behind the deal. The reason why ARPU is only $30-35 is that Eutelsat uses a wholesale distribution model. Comparing those ARPUs to ViaSat’s U.S. wholesale model, ViaSat may actually get more dollars per wholesale subscriber through Eutelsat than they do in the U.S. One of the main issues faced by Eutelsat is their terrible provisioning of the satellites’ capacity. Their wholesale agreements effectively closed off a large portion of their satellites’ throughput capacity and tied it to areas where they have no (or very poor) distribution agreements, such as in Eastern Europe and the Maghreb. ViaSat believes that proper satellite network management will increase the available throughput to the highest ARPU and return areas. As noted by ViaSat, when it comes to the U.S., the magic of their satellites includes the ability to steer spot beams to the areas with the highest level of demand, thereby increasing the effective utilization factor of the satellite.

The other nuance lost on Kerrisdale is that the JV will be a great boon to VSAT’s Commercial Networks segment. The JV will eventually involve the wholesale upgrade of Eutelsat’s ground and CPE network to be compatible with VSAT-3. It will lock in an EMEA infrastructure that will be specifically designed to support VSAT class satellites, to the detriment of all other competing designs and ensure ViaSat satellites are ordered in the future for any Eutelsat funded development program. ViaSat will gain a foothold in two very addressable markets: Eastern Europe and parts of the Middle East, where rural populations as a percentage of each region’s population are significantly higher than in the United States. ViaSat also gets a foothold in Europe to support transatlantic in-flight WiFi as well as added optionality on military networks to support NATO operations. Other intangibles not incorporated in the Kerrisdale model include regulatory assistance with orbital slots and each EMEA nation in which Eutelsat operates.

8. Lack of Economic Returns – Short Sighted and a “Duh” Statement

Kerrisdale’s claim that ViaSat has never generated “decent” ROIC is mostly a “duh” statement of fact. We wonder what business out there in the middle of a multi-billion dollar growth investment could manage a “decent” ROIC? Since WildBlue’s acquisition in 2009, ViaSat has spent roughly $2 billion on the construction, design, and launch of VSAT-1, VSAT-2, and now VSAT-3/4. Unfortunately for ViaSat’s ROIC, only one of those assets is producing cash profits at the moment. While Kerrisdale downplays individual project IRRs as the proper way to evaluate ViaSat’s steady state ROIC, we wholeheartedly disagree. That is the only viable method given the investment ramp going on. Their additional claims about low IRRs or “project IRRs continuing to decline” are predicated on their fallacious ARPU assumptions (as we’ve noted in Point #1) as well as a fundamental misunderstanding of what capital investment is necessary to serve 1-1.2mm customers in the United States. The only legitimate statement in their ROIC section was their admission that their IRR calculations are “purely theoretical”—a position we firmly agree with.

9. Some Glaring Omissions

However great the inaccuracies of the rest of their analysis, one of the main issues we have with Kerrisdale is their utter lack of understanding of the core legacy business. (Remember I used to work in the defense electronics business.) We don’t blame them, however, since the sell-side is guilty of this one-sided fascination with residential internet delivery as well. In their meandering 56-page report, Kerrisdale mentions the defense side just once, with three bullet points dedicated to a crown jewel business.

The defense business as a whole provides military satellite communications (system and service) to the military as well as tactical data link products that are head and shoulders above those of the competition (whether General Dynamics or L3). This business has compounded at a 17% revenue CAGR over the last fifteen years and has grown through the sequestration debacle of the previous six. That growth is only accelerating with higher-margin satellite services now offering up a massively expanded market opportunity for ViaSat and advancing their core capability set to a new level of competitive differentiation. To wit, backlog is up 40% year-over-year and has doubled since 2014.

I could spend more time on the mission critical, irreproducible nature of the product set, but the results and margins speak volumes. Kerrisdale either doesn’t understand or doesn’t want to mention that one of the key drivers of the economics of a long-term buildout of high throughput satellite systems is the ability to sell bandwidth to dedicated military applications. As mission parameters change in a more C4ISR (that’s Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance) world, the ability to broadcast encrypted, jam-resistant, high bandwidth data is going to be a game changing differentiator for future warfare and the next generation war fighter. While unpleasant to think about, it is an operational reality and a long-term secular trend that is only accelerating with the proliferation of artificial intelligence and unmanned hardware. What is the TAM for defense/government connectivity? Inmarsat and Intelsat currently peg this market at $4.8 billion. ViaSat’s share is somewhere around 1% at the moment. We value this business as a standalone entity at $35/share, using a forward acquisition multiple approach based on our FY18 numbers. Let’s be clear: Kerrisdale’s short has a target price of $35. The absurdity of that value is hopefully clear to everyone.

Other omissions, most likely from ignorance, include the lack of any mention of oil field services, maritime, or asset tracking applications. If you were to add up the current incumbent satellite revenue of those sub markets, you get an addressable market of $2-4 billion, depending on what you consider low-rate versus high-rate addressable. ViaSat’s current share? 0%. What we love here is the optionality embedded that no spreadsheet can ever truly incorporate.

In conclusion, we think $90 is a reasonable assessment of the fair value, based on what is currently on VSAT’s drawing board.

References

Ars Technica (2014, May 14). “Watch out for data caps: Video-hungry cord cutters use 328GB a month.”

Wired Business (2016, October 7). “New Data Caps Provide Another Reason to Hate Comcast.”

—

This report is published for information purposes only. You should not consider the information a recommendation to buy or sell any particular security, and this should not be considered as investment advice of any kind. The report is based on data obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed as being accurate and does not purport to be a complete summary of the data. Partners, employees, or their family members may have a position in securities mentioned herein.

Past performance is not a guarantee or indicator of future results. The opinions expressed herein are those of Cove Street Capital and are subject to change without notice. Consider the investment objectives, risks, and expenses before investing. These securities may not be in an account’s portfolio by the time this report has been received, or may have been repurchased for an account’s portfolio. These securities do not represent an entire account’s portfolio and may represent only a small percentage. You should not assume that any of the securities discussed in this report are or will be profitable, or that recommendations we make in the future will be profitable or equal the performance of the securities listed in this report. Recommendations made for the past year are available upon request.

CSC is an independent investment adviser registered under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, as amended. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training. Additional information about CSC can be found in our Form ADV Part 2a.